Knowledge Management in a hierarchical culture

The best definition of a Knowledge Worker is “someone who knows (or learns) more about their job than their boss does”. So how does this work in a hierarchy?

|

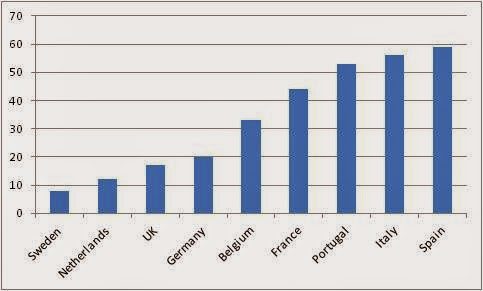

| Percentage of people in each country who agreed with the statement “It is important for a manager to have precise answers to most of the questions their subordinates may raise about their work”. |

The definition I use above means that the Knowledge Worker uses knowledge for their daily tasks. They do not blindly follow orders; they use knowledge to develop approaches and strategies for delivering their objectives. They are hired not just to do work, but to think as well. They make decisions for a living.

Knowledge Management aids the knowledge worker by providing them with the knowledge they need to do their job well and to make the correct decisions; this knowledge often having been developed through the collective experience of all the knowledge workers in the firm.

We can see the results above. Less than 10% of Swedes agreed with this statement, compared to nearly 60% of Spaniards. I suspect that in some of the more hierarchical non-European cultures, such as China, Russia, the Middle East, Japan and India, the proportions supporting this statement would be even higher. In these hierarchical cultures, “being the boss” equates with “having the answers”. This is of course crazy in a world of knowledge work, where the experience and knowledge lies in the community rather than the leadership.

So how do we address this conflict? I would suggest five approaches;

- Openly discuss the cultural issue, and the barrier this may cause to Knowledge Management, and therefore to the success of the knowledge-based business.

- Discuss the new role of the manager, which is to set the expectations and goals rather than to provide the answers.

- Develop the Knowledge Management Framework which allows the knowledge workers to find the answers they need.

- Educate the managers on the value of the KM Framework. Show them some examples and stories of the value it brings. Suggest to them that if a subordinate comes to them looking for an answer, their first response should be to ask “Have you used the KM system? What answers did you get?”

- Make sure the KM Framework supports the managers as well as their subordinates. Managers are knowledge workers too; they also make decisions based on knowledge. If the KM system provides them with better knowledge, and if they can see the advantages this brings, then they are more likely to promote this for their subordinates as well.

A hierarchy is a good way to assign authority and accountability, but should not be assumed to represent the way knowledge is distributed.

Tags: Archive, knowledge worker

Leave a Reply